Talk about noir. The BAFTA-nominated drama Southcliffe is dark, gloomy, bleak — a binge-watching version of rubbernecking.

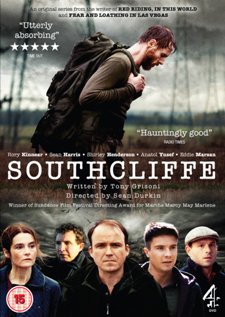

When Southcliffe premiered on the UK’s Channel 4 last August, most critics hailed the four-part miniseries as a triumph, describing it as “utterly absorbing” (Time Out), “hauntingly good” (Radio Times), and “a mesmerizing tragedy” (The Daily Telegraph).

It is all that… as well as confusing until you realize that its narrative is non-linear. At least that was the case for me when I first streamed it in London.

Here’s what Southcliffe isn’t: the tale of a mass shooting. That is the trigger, if you will, for the real story — the impact of the killings on the victims’ families and the Southcliffe community. The needless tragedy of it all. The pain, suffering, and grief. (If you’re thinking Broadchurch, it’s not that, either.)

The series opens with a woman getting shot while tending her front garden. A blurred image of a man walking toward her. More shots fired. A man running through deserted streets. Then reporter David Whitehead (Rory Kinnear, Penny Dreadful, The Mystery of Edwin Drood), a former Southcliffe resident, delivering a news broadcast about the shootings on telly.

The series opens with a woman getting shot while tending her front garden. A blurred image of a man walking toward her. More shots fired. A man running through deserted streets. Then reporter David Whitehead (Rory Kinnear, Penny Dreadful, The Mystery of Edwin Drood), a former Southcliffe resident, delivering a news broadcast about the shootings on telly.

Cut to Stephen Morton (Sean Harris, Prometheus, The Borgias), running home in a pair of military fatigues and helping his invalid mum out of bed, followed by a celebration for local soldiers, including Chris Cooper (Joe Dempsie, Game of Thrones, Skins), returning home from Afghanistan. The two men meet at a pub, where Morton has introduced himself as a commander from the Gulf War. Their conversation leads to one event, and then another, the latter of which sets off Morton’s subsequent killing spree.

Men, women, and children are all victims. Killed at random. Those left shaken and shattered include pub owner Paul Gould (Anatol Yusef, Boardwalk Empire, Trial & Retribution), working-class couple Claire (Shirley Henderson, The Crimson Petal and the White, The Way We Live Now) and Andrew Salter (Eddie Marsan, Ray Donovan, Little Dorrit), and Cooper. Whitehead, too, does not escape unscathed, albeit not as a bereaved loved one.

In the aftermath, of the five stages of grief, denial is more prominent for some than others. Anger is felt by all. Bargaining takes the form of hysteria for one. Depression and acceptance come sooner for few.

The acting in Southcliffe is truly stellar, and evidenced by Harris’ BAFTA win for Best Actor and BAFTA nominations for Kinnear and Henderson for Best Supporting Actor and Actress, respectively. (That Henderson didn’t bring home the award for her outstanding performance was just criminal.)

Likewise, the setting could not have been more appropriate. If sunshine ever graces the skies of southeast England, you wouldn’t know it from Southcliffe. The gloomy, rainy, foggy skies and muddy walkways offer a palette of various shades of grey (perhaps 50) and nothing more. Even the green of the marshes is tinged, its vibrancy muted, if not in its actual color than in the mood it evokes.

And it is the literal and figurative greyness that is pervasive throughout Southcliffe. Call it depressing. If you do, the series will have elicited the thoughts and feelings of utter despair and sorrow from senseless acts that were meant to arise from watching it. For viewers who prefer watching events unfold in sequence, know that the non-linear timeline isn’t important to the story itself but to the telling of it, with its cutting back and forth between pre- and post-rampage scenes symbolic of the nature of human beings.

Southcliffe is now streaming in the US exclusively at Netflix.

__________________

Add your comments on our Facebook, Google+, and Twitter pages.